About Fishwise

FishWise, founded in 2002, is a nonprofit marine conservation organization based in Santa Cruz, California. FishWise promotes the health and recovery of ocean ecosystems by providing innovative market-‐based tools to the seafood industry. The organization supports seafood sustainability through environmentally responsible business practices. FishWise is a founding member of the Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions, with staff serving on the Environmental Stakeholder Committee of the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF), the Fisheries Advisory Council of Fair Trade USA, and participates in a variety of other industry and marine conservation initiatives. FishWise works with companies throughout the supply chain and is currently partnered with several of North America’s largest retailers, including Safeway Inc., Target Corp., and Hy-‐Vee Inc. Through its relationships with retailers and suppliers, FishWise works with over 65 million pounds of seafood per year and more than 100 species from farmed and wild sources. Its retail partners maintain more than 3,700 storefronts in North America.

About this document

This white paper on human rights in the seafood industry follows FishWise’s white paper on seafood traceability. It is hoped that this document will create connections across businesses, organizations, and governments to spark conversation and action as to how the seafood industry can work together to eliminate human rights abuses and illegal products from supply chains. If all stakeholders work together to elevate these issues of human dignity, and incorporate them into business practices, human rights within the seafood industry can be improved significantly.

©2013 FishWise. All rights reserved. Sections of this report may be copied with permission of FishWise. Please acknowledge source on all reproduced materials.

Definitions

Labor Rights

In this paper, labor rights refer to a broader category of issues than trafficking or modern slavery. The International Labour Organization’s (ILO) ‘Declaration of the Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work’ places these rights into core standards: freedom of association, right to collective bargaining, prohibition of forced labor, elimination of the worst forms of child labor, and non-‐discrimination in employment (ILO 1998).

Forced labor

Forced labor is any working condition under which an individual is threatened or coerced to act against his or her will. Threatening or coercive working conditions nullify any prior consent-‐to-‐work agreements or contracts between victim(s) and employer(s) (USDOS 2013).

Human trafficking

According to the 2013 U.S. State Department’s 2013 Trafficking in Person’s Report (hereafter, TIP report), ‘Human trafficking’ and ‘trafficking in persons’ are umbrella terms for “the act of recruiting, harboring, transporting, providing or obtaining a person for compelled labor or commercial sex through the use of force, fraud, or coercion” (USDOS 2013). Trafficking victims can include both individuals smuggled across borders and those born into state servitude (USDOS 2013). At the core of this issue is the traffickers’ intention to exploit or enslave another human being, and the coercive, underhanded practices they engage in to do so (USDOS 2013).

The international definition set forth by the United Nations (UN) Office on Drugs and Crime (ODC) defines Trafficking in Persons as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation” (UNODC 2013).

Smuggling of migrants

The United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime defines ‘smuggling of migrants’ as “the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident” (UN 2001).

Modern Slavery

This is a general term often used when referring to holding a person in compelled service, including trafficking, forced labor, involuntary servitude, and bonded labor (US DOS 2013b).

Human and Labor Rights Abuses in Seafood Supply Chains

Background

It is estimated that the livelihoods of 10-‐12% of the world’s population (660-‐820 million people) are directly or indirectly dependent upon marine capture fisheries and aquaculture, which produce over 90 million tons of fish every year (FAO 2012). While the majority of the seafood industry operates legally and employs fair labor practices (FAO 2012; ILO 2013), a number of publications have recognized and documented the pervasiveness of human trafficking, forced labor, child labor, and egregious health and safety violations in marine capture, aquaculture, and seafood processing operations (Pearson et al. 2006; Skinner 2008; Brennan 2009; UNIAP 2009; EJF 2010; Robertson 2011; Stringer et al. 2011; Motlagh 2012; PBS 2012; Sifton 2012; PBS 2012; Surtees 2012; EJF 2013; IEDE 2013; ILO 2013; ILRF/WWU 2013; Stringer and Simmons 2013; Stringer et al. 2013).

About 660-820 million people are directly or indirectly dependent upon marine capture fisheries and aquaculture.

While forced labor and human trafficking in fisheries and aquaculture is not a new phenomenon, the problem has been exacerbated in recent years by globalization of the seafood industry; illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU) fishing; increased competition for marine resources; and the availability and mobility of low-‐cost migrant labor (ILO 2013). Both genders are involved in the seafood industry. Victims on board fishing vessels are primarily men and boys ranging from age 15 to over 50 (UNIAP 2009; Surtees 2012). Processing facility workers are most often women and girls (Sifton 2012; IEDE 2013; ILRF/WWU 2013).

Globally, it is estimated there are over 20 million people working under coercive or forced labor conditions -‐ primarily migrant workers in labor-‐intensive industries in the informal (e.g. untaxed and undocumented sectors) and black-‐market (e.g. trade in illegal goods) economy (ILO 2013). The recruiting processes and working conditions of many fishers and seafood industry employees are so egregious that these human and labor rights abuses have been referred to as ‘modern slavery’ (EJF 2010; ILO 2013). Case studies from the last decade cite examples of fraudulent and deceptive recruiting, 18 - 20 hour workdays, homicide, sexual abuse, child labor, physical and mental abuse, abandonment, refusal of fair and promised pay.

Over 20 million people working under coercive or forced labor conditions such as 20 hour workdays, homicide, child labor.

Abuse Aboard Fishing Vessels

Some of the worst human rights and labor violations in the seafood industry occur onboard fishing vessels (ILO 2013). Violations are often committed by the senior crew and captain (ILO 2013). Case studies from the last decade cite examples of recruitment under false pretenses, 20 hour workdays, child labor, physical and mental abuse, abandonment, and withholding of pay and identifying documents (Skinner 2008; EJF 2010, 2013; ILO 2013). In one report, over half the victims interviewed reported seeing a fellow crewmember murdered (UNIAP 2009).

Abuse in Seafood Processing

Most case studies of labor and human rights abuses in seafood processing and packaging involve migrant workers in both licensed and non-‐licensed operations in the southern provinces of Thailand (UNIAP 2009; Sifton 2012; ILRF/WWU 2013; IEDE 2013). As previously mentioned, migrant labor is used to cut costs and to fill the void created by a lack of available Thai workers. Some of the most egregious abuses occur in the Thai shrimp industry which is highly dependent upon migrant labor, including the use of underage workers, refusal of pay, charging workers excessive fees for work permits, and an ineffective auditing regime (ILRF/WWU 2013; Westlund 2013).

Four hundred thousand Burmese migrants work in Samut Sakhon, where 40% of Thailand’s shrimp is peeled and frozen for export (Motlagh 2012). Around 200 peeling sheds are officially registered with Thailand’s Department of Fisheries. Less than 100 peeling sheds are also registered with Thai Frozen Foods Association, even though registration is required to legally supply to other members and export to international markets (EJF 2013b). Estimates for unregistered peeling sheds operating in Samut Sakhon range from 400 to 1,300, with some organizations putting the number closer to 2,000 (EJF 2013b; Motlagh 2012). These unregistered facilities are not subject to any regulation or oversight, and are where the most severe abuses occur.

Estimates for unregistered peeling sheds operating in Samut Sakhon range from 400 to 1,300, with some organizations putting the number closer to 2,000.

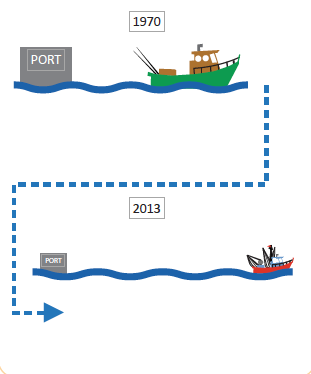

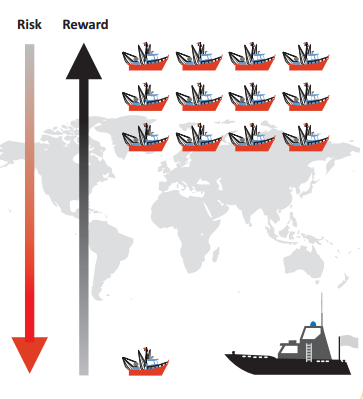

1) Overfishing has led to a global decline of marine fish stocks, increasing the competition for marine resources.

2) In order to find more plentiful fishing grounds, vessel operators are forced to travel further out to sea, or to remote regions, for longer periods of time.

3) The global nature of the seafood industry combined with poor enforcement creates a low risk/high reward scenario, allowing for human rights abuses and illegal fishing to go undetected.